Bate, Bate, Chocolate

I find that I talk about food in my classroom all the time. It’s one common thing that unites all culture and peoples around the world because we all love to eat! Even my English language learners who might be brand new to the country learn food words really fast because they encounter them every day. It’s a universal connector! I especially love finding songs and poems from different cultures that talk about preparing, making, baking, eating, or serving food.

This traditional poem from Mexico talks about making hot chocolate, something that my kids LOVE to drink. However, the way that hot chocolate is traditionally made in Mexico is pretty different from the way that my students typically make hot chocolate at home. In this lesson we learn the poem and actions but also make connections to a story and a culture that kids might not have experienced before.

How do you make hot chocolate?

I start out by asking kiddos how they make hot chocolate at home. A lot of them come back with stories about using hot chocolate powder and mixing it with hot milk or water that they heat up in a kettle or in the microwave. Some kids will talk about using those hot chocolate bombs which are essentially chocolate spheres filled with marshmallows and powder and sugar that turn into hot chocolate when you pour warm milk or water over them. Very few kiddos talk about heating up milk or water on the stove in a sauce pan. For my Midwestern kiddos, hot chocolate powder is the norm.

Then I talk a tiny bit about the origins of hot chocolate and where chocolate itself comes from. Many folks trace chocolate back to Mexico and the Mayan and Aztec people. Stories tell us that ancient civilizations in Mexico would make all sorts of drinks using the cocoa beans and actually cocoa had an important role in Mayan mythology. Some stories tell us that the ancient Mayans would use cocoa beans as currency and would use them to trade and barter. Chocolate and the cocoa bean have a very fun history but for the sake of my lesson I focus on telling the kids that cocoa beans and the origins of chocolate come from Mexico.

“Since drinking chocolate started in Mexico then we should learn a poem about making chocolate that comes from Mexico.” Then I have to explain how hot chocolate is made in Mexico (at least the traditional way). It doesn’t start with powder or a kettle or a hot chocolate bomb but with a piece of hard chocolate and a special tool called a molinillo. You put some milk in a saucepan and heat it up on the stove. Then break off as much chocolate as you need and put the hard chocolate in the warm milk. The chocolate will melt into the milk and you can add things like cinnamon, sugar, or even chili powder. Then you have to mix it all together with your molinillo!

A molinillo is a traditional turned wood whisk used in Latin America, as well as the Philippines, where it is also called a batirol or batidor. A molinillo is primarily used for preparing hot beverages such as hot chocolate, atole, cacao, and champurrado. Just hold the molinillo between your palms and twist it by rubbing your palms together. When you spin the molinillo the rotation mixes all the ingredients in your drink and creates a frothy foam.

You can absolutely buy a molinillo online in a variety of places but that can be pretty expensive. The cheapest one I could find on Amazon was about $12. I’d suggest you go to your local Latin Grocery store and look there. My local grocery store chain has a big section specifically for Mexican food and traditional Latin dishes and they had molinillos for $4.

I take the time to talk through this hot chocolate process with kiddos because most of them have never made hot chocolate this way. If I barreled right into the poem they would probably be able to learn the words but I don’t think they’d have the context for the words to make any sense. Any time I teach a song or poem with new words or new experiences I make sure to take the time to explain what those words mean.

Bate, bate – Teaching the Poem

At this point I jump in to teaching the poem. In English we often syllabify “chocolate” in two syllables and it sounds like “choc-let.” In Spanish it sounds like “cho-co-la-te,” when ends up being four syllables. We count how many syllables there are and speak through each one. I usually hold up four fingers and speak one syllable as I point to each finger. Then I might quiz kids by pointing at one of my fingers and asking kids which syllable goes with each one. We spend just a minute going through this process and then add a bit more.

I tell kid that speaking this poem is as easy as “One, two, three! In fact, let’s try that!” So we say “one two three, cho. One two three, co. One two three, la. One two three, te.” But since the poem is originally from Mexico we can’t speak the “one, two, three” in English but should probably do it in Spanish. So we switch out the English for Spanish and say “Uno, dos, tres, cho. Uno, dos, tres, co. Uno, dos, tres, la. Uno, dos, tres, te.”

Before moving on I’ll challenge the kids to do the numbers all on their own and I’ll say the “cho-co-la-te” on my own. We go back and forth with the kids counting the numbers and me adding in the syllables for “chocolate.” Then we switch parts and I speak the numbers where they as a group speak the syllables. This is a little tricker for them but I find that if I put up “cho-co-la-te” on the white board or use my fingers to remind them of the four syllables things are a little easier.

Then we add in the rest of the poem and the mixing of the hot chocolate. The first part of the poem goes “Bate, bate, chocolate,” with that phrase repeated two or four times (depending on your preference). Bate translates from Spanish to mix or stir. When I talk through this with kids they get the words pretty easily and usually add the action of taking a spoon to mix up the hot chocolate. That’s when I pull out the molinillo and show them how it works. Our action of stirring changes from a wooden spoon mixing action to the spinning of a molinillo. That’s when we put it all together.

Bate, bate, chocolate.

Bate, bate, chocolate.

Bate, bate, chocolate.

Bate, bate, chocolate.

Uno, dos, tres, cho.

Uno, dos, tres, co.

Uno, dos, tres, la.

Uno, dos, tres, te.

And you can finish with chanting “cho-co-la-te” four times if you want.

We speak through the poem a couple times doing the words all together and adding in the actions including spinning molinillos for the A section and counting on our fingers for the B section. One year I thought it would be a fun idea to hand out rhythm sticks or mallets for kids to use as their own pretend molinillo but that sort of devolved into chaos. Do not recommend. 😀

Usually after this we’ll try the poem a variety of different ways. We’ll speak the A section together and then on the B section will split up with kids speaking the numbers and me saying the “cho-co-la-te,” or vice versa with kids on syllables and me on numbers. Then I’ll split up the class and half will do the syllables while the other half do the numbers. Then switch. There’s a lot of variety and options here for practicing this split part. Partners? Sure. Front and back of class? Sure. Whatever you want!

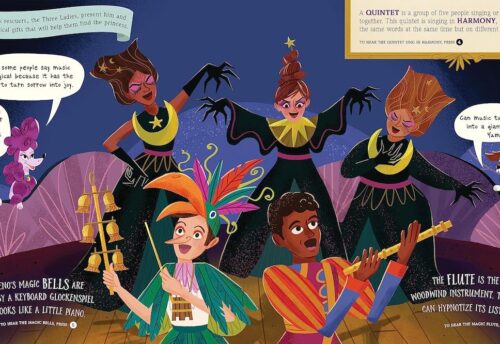

Another fun variation I took one year was to add instruments into the mix. I pulled out a scraper, shaker, wood, and metal instrument and assigned one to each of the syllables. Then in the B section whenever you said “cho” a wood block would play and when you say “co” an egg shaker, and so on. On the A section I let all kids play and keep the steady beat however their instrument would allow. After one time through the poem we’d all rotate so that kids were able to cycle through all the instruments before the lesson was over.

Extras and Extensions

What else? Well there are some really wonderful videos out there to help expand and bolster this lesson. I have a couple favorite videos that I use to help explain how hot chocolate is traditionally made in Mexico. Again, if I’m going to introduce a new concept, idea, or vocab word I want kids to know the meaning. I can’t take them all to a kitchen and make hot chocolate but I can easily show them a 2 minute (or less!) video that explains how it all works.

One fun video that I just found is this video from PBS where a storyteller explains in Ensligh and Spanish how to make hot chocolate and holds a molinillo. Unlike the other videos showing how hot chocolate is made this isn’t an actual video making hot chocolate but just explains how it works as if we’re sitting in the storyteller’s classroom.

Another fun video I love to show is this one by José-Luis Orozco where he turns the traditional poem into a song and intersperses videos of someone making hot chocolate. The kids love to watch and sing along. Since there are kids in the video who sing with José-Luis I tell my students to sing whenever the kids on screen sing.

I just learned about this fun book called “Grandma’s Chocolate/El Chocolate De Abuelita” which, among other things, explains making hot chocolate the Mexican way. Little Sabrina is playing with her Grandma and pretends to be a Mayan princess. Sabrina discovers that “chocolate is perfect for a Mayan princess.” As Sabrina and her Abuelita play and make hot chocolate they share the history and customs of the native peoples of Mexico.

If you want to see a video explanation of this process you can follow this link to a Musical Mondays video where I talked specifically about this lesson and how I make it work in my classroom.

What do you do when you teach this poem? Do you have favorite resources or ideas that you use every time? Add your ideas below in the comments so that other folks can try them out too!

Leave a Reply