Rhythm Syllable Systems – What to use and why!

What do you call a quarter note? In your classroom do you call it “Ta”? Or Maybe you call it “Du”. What about other rhythms? Do you say “Ta, Ti-ti” or maybe “Du, Du-de” or even “Ta, Ta-di.” Perhaps you just call them “pal, buddy” or go right to numbers “1, 2-and” or some other set of words and phrases. The next question is why. Why do you choose to teach using that rhythm syllable system? Is this what you’re most familiar with? Maybe this is just what you learned when you were in elementary school and it’s easiest for you. Or is this the system that you heard at a workshop or maybe in your elementary methods class in college? There are a lot of options out there when it comes to rhythm syllable systems with pros and cons for each. How did they develop? What system works best? Why does one person prefer “ti-ti” over “ta-di”?

What do you call a quarter note? In your classroom do you call it “Ta”? Or Maybe you call it “Du”. What about other rhythms? Do you say “Ta, Ti-ti” or maybe “Du, Du-de” or even “Ta, Ta-di.” Perhaps you just call them “pal, buddy” or go right to numbers “1, 2-and” or some other set of words and phrases. The next question is why. Why do you choose to teach using that rhythm syllable system? Is this what you’re most familiar with? Maybe this is just what you learned when you were in elementary school and it’s easiest for you. Or is this the system that you heard at a workshop or maybe in your elementary methods class in college? There are a lot of options out there when it comes to rhythm syllable systems with pros and cons for each. How did they develop? What system works best? Why does one person prefer “ti-ti” over “ta-di”?

In this blog post I’d like to look at several different rhythm syllable systems that are generally used and explore some pros and cons for each method. I absolutely believe that each one of us should sit down and think through what syllable system we’re using and how it benefits our students (or not). “Because I’ve always done it that way” is not a good enough reason to continue doing something. So, no matter what rhythm syllable system you currently use, read through and decide what you think would work best for you and your students.

What is a Rhythm Counting System?

Before we get into variations, let’s talk about why people us a rhythm syllable system at all. Rhythm syllables were developed so that students could have a musical way to read rhythm. The ideas is that this system could get away from mathematical counting (which feels unmusical) while still showing durations and relationships between notes. A rhythm syllable system gives the student a set of nonsense syllables or sounds to associate with written notation and beat formations. Just as solfege syllables (Do, Re, Mi) give the student a tangible thing to say or think when representing an interval or set of pitches, a rhythm syllable system gives the student an easy way to understand note value. Being able to “think/audiate” in rhythm syllables also helps students to decode rhythms that they hear, making dictation/memorization/performance much easier.In the United States, the generally accepted norm is that students will eventually transfer from a rhythm syllable system (like Ta, Titi) to a number system of counting (1-e-&-a). Often times the rhythm syllable system will last through 3rd or 4th grade and in some cases even into middle or high school. For better or for worse, eventually most students in the US transfer to a more mathematical number system based around numbers and subdivision. It’s unclear how or when this shift to a number system became so widely accepted or if there was any specific thought as to why this system might be the best to end up with. It might be that this system benefits instrumentalists as it came to prominence with the rise of public school instrumental music programs at the end of the 19th century. In any case, rhythm syllable systems are most commonly found in elementary schools and last for several years until they are replaced by a number counting system at the middle or secondary levels.

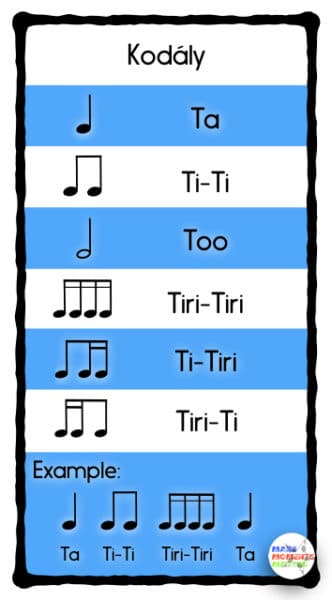

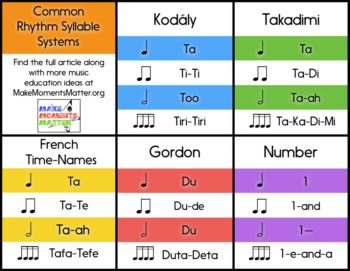

Kodály – Ta, Ti-ti, Tiri-Tiri

This system seems to be the most wide-spread rhythm syllable system in the US and comes from the work and teachings of Kodály. There are many variations to this system, but rhythm counting that centers around “Ta, Ti-Ti” seems to be pretty widely used and accepted. Every quarter note is called “Ta” and eighth notes are called “Ti-Ti.” It seems that sixteenth notes were originally called “Tiri-Tiri” but often are replaced with the syllable “Tika-Tika.” If this system really did originate with Kodály, one might speculate that “Tiri” was easier to say and flowed better with the Hungarian/European languages. The shift to “tika” might have been because it is easier for speakers of English or it might just translate better to the creation of sound and articulation of wind instruments.In this system each note value has its own particular sound no matter where the “tactus” (the accented rhythm/macrobeat) might be. Quarter notes are “Ta” but eighth notes are “Ti” and sixteenth notes are “Tir.” Some would say that there is no internal consistency with this system reasoning that distinct names for each note value (Quarter note-Ta, Eighth notes-Ti-Ti) makes a note value easy to recognize, but this variation makes it difficult to relate each note to the tactus or accented beat. Some might say that this makes it easier to lose the pulse of the rhythm. The Kodaly system is often compared against the Gordon or Takadimi systems (for more on this, read on!).

Further Reading:

”Traditional Kodály Rhythm Syllables: Taking a New Look” by Jonathan C. Rappaport published in the Kodály Envoy

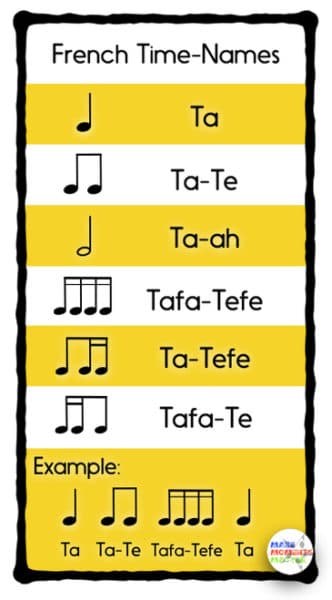

French Time-Names System – Ta, Ta-Te

This is one of the earliest known systems for rhythmic training and was developed in the early nineteenth century in France. This system of rhythm reading was named the French “Time-Names system”, and also sometimes called the “Galin-Paris-Cheve system.” Originally notes were counted using a French word for a duration regardless of the meter. For example, “noir” (black) is said for each quarter note, two eighth-notes are “cro-che” (eighth-note), a half·note is “bla-anch” (white), and four sixteenth notes are counted “dou-ble cro-che” (double eighth-note). Taken together, any given simple rhythm can be spoken and then performed using these patterns easily and fluidly.

This is one of the earliest known systems for rhythmic training and was developed in the early nineteenth century in France. This system of rhythm reading was named the French “Time-Names system”, and also sometimes called the “Galin-Paris-Cheve system.” Originally notes were counted using a French word for a duration regardless of the meter. For example, “noir” (black) is said for each quarter note, two eighth-notes are “cro-che” (eighth-note), a half·note is “bla-anch” (white), and four sixteenth notes are counted “dou-ble cro-che” (double eighth-note). Taken together, any given simple rhythm can be spoken and then performed using these patterns easily and fluidly.

Toward the middle of the nineteenth century the American musician Lowell Mason (affectionately named the “Father of Music Education”) adapted the French Time-Names system for use in the United States. Instead of using the French names of the notes, he replaced these with a system that identified the value of each note within a meter and the measure.

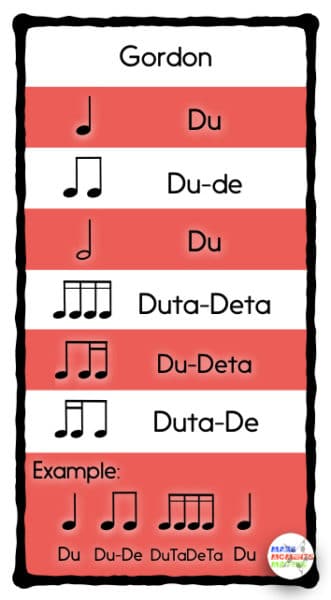

Gordon – Du, Du-De

In contrast to some of the other systems in use, this rhythm counting style is actually quite new. In 1993, Edwin Gordon (commonly associated with Music Learning Theory) adapted several other systems and synthesized a rhythm syllable system that he began to use. While this system is often named after Edwin Gordon, James Froseth and Albert Blaser also contributed to its development and elements were borrowed from Froseth’s stand-alone system and the counting system of the Eastman School of Music (both of which are not mentioned in this blog post).In Gordon’s approach, the beat is counted as “du” and subdivided as “du-de” and further subdivided as “du-ta-de-ta.” There are many out there who would argue that the Gordon system “is easier to pronounce, and is well suited for instrumental music instruction,” because it uses consonants more closely imitating the articulation movements of the tongue for playing wind instruments.

Whether you believe this system is “easier to pronounce” or not really depends on you. Personally I think something like “tika-tika” or “Takadimi” is easier to pronounce quickly than the Gordon, “Dutadeta,” but I have a choral and vocal music background and I feel like the harder “ta” and “ka” are easier to say quickly than “du” and “de.” Other friends of mine who play brass instruments tend to agree saying that “tika-tika” and “takadimi” lead well into triple tonguing in brass instruments. The decision about whether something is more or less easy to pronounce apparently depends on your own subjective background and context.

Further Reading:

Gordon Rhythm Counting – GIML Website

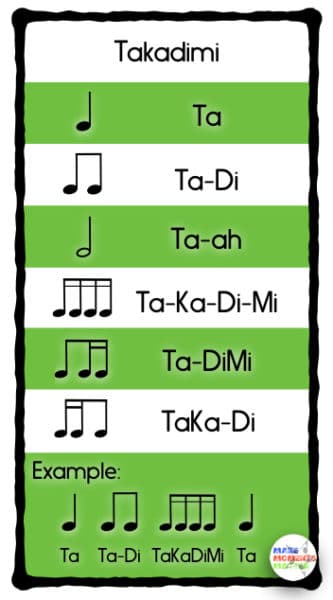

Takadimi

Takadimi is a system devised by Richard Hoffman, William Pelto, and John W. White in 1996 in order to teach rhythm skills. Takadimi, while utilizing rhythmic symbols borrowed from classical South Indian carnatic music, differentiates itself from this method by focusing the syllables on meter and on western tonal rhythm. In the Takadimi system the beat is always voiced with ta. The division and subdivision are always ta-di and ta-ka-di-mi. With this system, emphasis is put on the tactus or macrobeat and in many ways it relates to the work that Gordon and others did on their own systems. However, Hoffman, Pelto, and White believe that they took the best from many existing systems and tweaked them together to form this system that best meets the goals they set for themselves.Takadimi is similar to the Kodály Method, developed in 1935 in Hungary and both systems can be traced back to the 19th century French Time-Names system. The system developed by Hungarian composer Kodály differs from Takadimi in that is ascribes syllables to specific notational values, regardless of their placement within the beat. For example, an eighth note is called ‘ti’ whether it is on the attack/tactus of the beat or in the middle. It is also called ‘ti’ regardless of the meter. Some argue that the Kodály method was intended for use at the elementary level, and many critics say that it is not expandable to upper level classrooms. Philip Tacka and Michael Houlahan, experts who have studied Kodály at Millersville University, have stated that “the Takadimi rhythm system solves the problems associated with the Kodály rhythm syllables. We believe that were Kodály alive today, he would certainly encourage his students and colleagues to use the Takadimi system.”

Further Reading:

Takadimi – Learning Rhythm with Takadimi

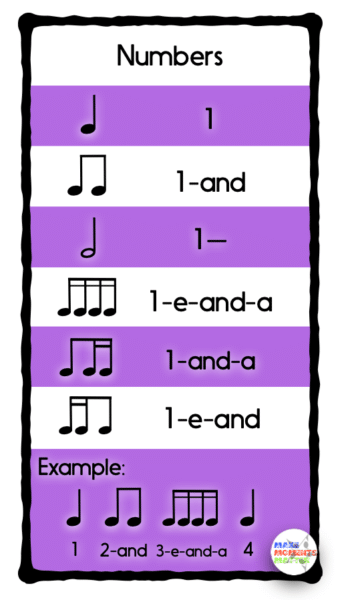

Numbers – 1-e-&-a

In contrast to the European-influenced traditional models mentioned above, many music educators in America offer a vastly different approach to mnemonics or neutral syllable systems. While the systems described above have been used for over a hundred years, and are widely accepted in certain circles, a large number of American music educators use a more mathematical approach to learning rhythms. As I said before, this system is widely-accepted in the US at the secondary level and most musicians in instrumental settings in the United States have used this (or a version of rhythmic counting and reading) at some part of their music training.This system is based on numbers and counting each of the main macrobeats. For example, four quarter notes in 4/4 time would be counted as “1-2-3-4,” and six eighth-notes in 6/8 time would be counted as “1-2-3-4-5-6.” Subdivision of the beat are counted as “and,” and further subdivisions are “e” and “a,” so that four sixteenths would be counted as “1-e-and-a.”

In contrast to the European-influenced traditional models mentioned above, many music educators in America offer a vastly different approach to mnemonics or neutral syllable systems. While the systems described above have been used for over a hundred years, and are widely accepted in certain circles, a large number of American music educators use a more mathematical approach to learning rhythms. As I said before, this system is widely-accepted in the US at the secondary level and most musicians in instrumental settings in the United States have used this (or a version of rhythmic counting and reading) at some part of their music training.This system is based on numbers and counting each of the main macrobeats. For example, four quarter notes in 4/4 time would be counted as “1-2-3-4,” and six eighth-notes in 6/8 time would be counted as “1-2-3-4-5-6.” Subdivision of the beat are counted as “and,” and further subdivisions are “e” and “a,” so that four sixteenths would be counted as “1-e-and-a.”

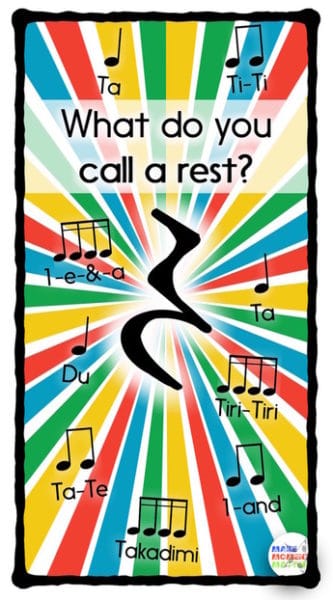

What to do with a Rest?

Some teachers tell student to just be silent during rests, but that doesn’t help them feel the beat or understand the duration of the beat. Often with this approach students start to “clip off” the ends of the rests and therefore start to go faster and faster. They don’t have a tangible way to feel that beat of silence. Other people teach students to say “Shhh” during a rest but that is also problematic. A rest is supposed to be a beat of silence, but making a sound like “shhhh” during the rest takes out that silence. Maybe one could start at young ages with something like “shhhh” but then eventually transition to a beat of silence once kids have a handle on feeling the inner pulse and giving the rest its space.I’ve thought a lot about the various ways to teach a rest and I eventually decided to teach rest the way that my mentor teacher, Debbie Gray, teaches her students. She says that whenever they see a rest they can say the name of the rest (for a quarter note, this would be “ta”) but they just can’t let the sound out of their mouth. I suppose this sort of syncs up with the Gordon/MLT idea of audiation and thinking the sound in your head instead of actually vocalizing it. To make it really fun, Debbie tells students that they can even shout the rest as long as they keep all the sound in their mouth and don’t let anything out. This results in a class full of students “silent shouting” out a rest. It doesn’t completely solve the rest conundrum, but it does give students a way to feel the full duration of the note value in their head as they make the action of shouting/speaking silently.

Conclusion – The Choice is YOURS!

It is clear that there are many rhythm syllable systems for music educators to choose from, based on their personal teaching philosophy. Each approach is different yet accomplishes the same main goal: teaching rhythm. I want to add a little disclaimer here to just say that I personally do not think that one rhythm syllable system is superior to another. I know there are music professors and pedagogs out there who could argue for hours over why their preferred system is superior and better for instruction. But I would say that their system is just that: preferred. There is no one syllable system that is best for all students everywhere, forever and ever, amen. Each of us teaches in a specific context and has our own diverse school population with unique experiences and circumstances.I would also say that kids are highly adaptable. When I was a first year teacher I started out in a school and had no idea what the teacher before me said when teaching rhythms. Heck, I barely knew how to teach rhythms at all, what rhythms were appropriate for each age, and where to start. I did some research, figured out what rhythm system I liked the best (and why), and then went for it. My student’s had not read rhythms like this before but lo and behold, within a few weeks they were going strong. No one was emotionally scared for life because I taught “Ta-di” instead of “Ti-ti.” They figured out the change and adapted.

Further Reading and References

Okay, I think that I’ve covered all the big and widely-accepted methods of rhythm syllables. I hope to write in the future about the Orff approach to teaching rhythm reading and maybe even share which rhythm syllable system I use and why…Do you say something different or a variation of one of the approaches above? Leave a comment and let me know! I’d especially love to talk with anyone who uses the French Time-Names system because I think it is so unique and fascinating!

“Syllable Systems: Four students’ experiences in learning rhythm” a Master’s Thesis by Tammy Renee FustA Review of Rhythm Syllable Systems – blog post by Dr. Robert Adams

Pingback: Music Literacy: Steps for Reading Music – FrauMusik

Pingback: How to Read Complex Rhythms - Piano Sight Reading

Pingback: A Deep Dive into Hart Rouge's Vichten for Choirs - Inspired Choir

Pingback: Fun Sequential Lessons are Key to Teaching Music Reading

Pingback: Note Reading In Music In Three Easy Steps - Sunshine and Music